It is no secret that AI technologies are anticipated to deliver a wide range of economic and societal benefits across various sectors, such as environment and health, public services, finance, transportation, home affairs, and agriculture. Indeed, they excel in enhancing prediction accuracy, optimizing operations, resource allocation, and tailoring services to individual needs.

However, the safety concerns for users when AI technologies are integrated into products and services are causing apprehension at all levels of society.

Indeed, as we know, AI systems have the potential to compromise rights like non-discrimination, freedom of expression, human dignity, personal data protection, and privacy.

With the rapid advancement of AI, regulatory frameworks have become a focal point in the European Union and policymakers have been committed to establishing a 'human-centric' approach to AI to ensure that Europeans can leverage new technologies that align with the EU's values and principles.

In its 2020 White Paper on Artificial Intelligence, the European Commission vowed to promote AI adoption while mitigating risks associated with certain applications. Initially, the Commission released non-binding Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI and policy recommendations, but later transitioned to a legislative approach, advocating for harmonized rules governing the development, market placement, and use of AI systems.

Introducing the EU AI Act

In December 2023, European Union legislators reached a consensus on the draft AI act. Introduced by the European Commission in April 2021, the AI act represents the first globally binding horizontal regulation on AI, establishing a unified framework for the utilization and distribution of AI systems within the EU.

How will the EU AI Act be implemented?

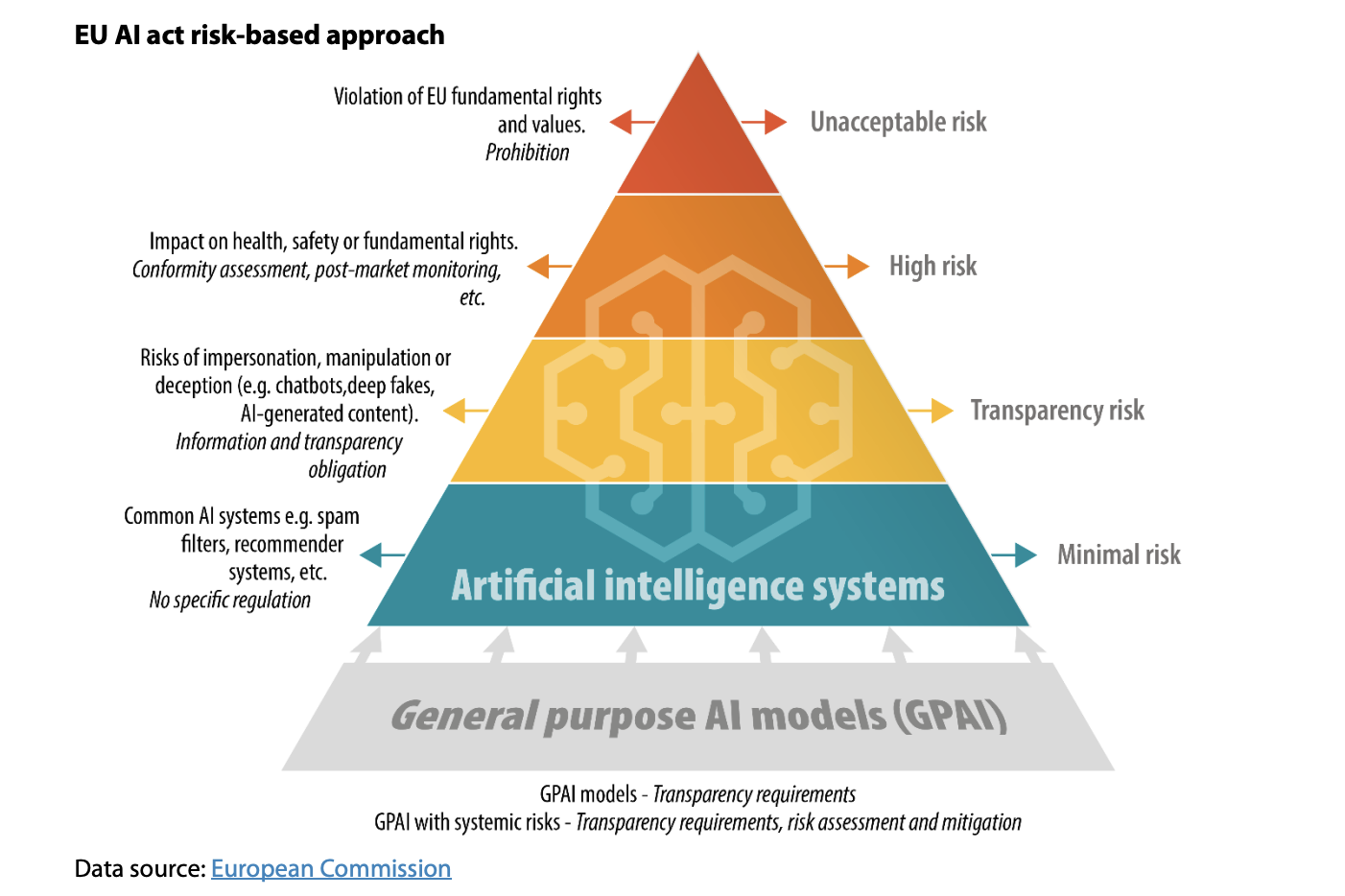

In essence, the EU AI Act categorizes AI systems based on varying requirements and obligations tailored through a 'risk-based approach.'

(For correctness' sake, the below classification and illustration is taken directly from the original text)

A. Prohibited AI practices (Unacceptable risks):

The final text prohibits a wider range of AI practices as originally proposed by the Commission because of their harmful impact:

- AI systems using subliminal or manipulative or deceptive techniques to distort people's or a group of people's behaviour and impair informed decision-making, leading to significant harm;

- AI systems exploiting vulnerabilities due to age, disability, or social or economic situations, causing significant harm;

- Biometric categorisation systems inferring race, political opinions, trade union membership, religious or philosophical beliefs, sex life, or sexual orientation (except for lawful labelling or filtering in law-enforcement purposes);

- AI systems evaluating or classifying individuals or groups based on social behaviour or personal characteristics, leading to detrimental or disproportionate treatment in unrelated contexts or unjustified or disproportionate to their behaviour;

- 'Real-time' remote biometric identification in public spaces for law enforcement (except for specific necessary objectives such as searching for victims of abduction, sexual exploitation or missing persons, preventing certain substantial and imminent threats to safety, or identifying suspects in serious crimes);

- AI systems assessing the risk of individuals committing criminal offences based solely on profiling or personality traits and characteristics (except when supporting human assessments based on objective, verifiable facts linked to a criminal activity);

- AI systems creating or expanding facial recognition databases through untargeted scraping from the internet or CCTV footage;

- AI systems inferring emotions in workplaces or educational institutions, except for medical or safety reasons.

Prohibited systems will have six months to be phased out within the act coming into effect.

B. High-risk AI systems

The AI act identifies a number of use cases in which AI systems are to be considered high risk because they can potentially create an adverse impact on people's health, safety or their fundamental rights.

The risk classification is based on the intended purpose of the AI system. The function performed by the AI system and the specific purpose and modalities for which the system is used are key to determine if an AI system is high-risk or not. High-risk AI systems can be safety components of products covered by sectoral EU law (e.g. medical devices) or AI systems that, as a matter of principle, are considered to be high-risk when they are used in specific areas listed in the EU AI Act annex.

The Commission is tasked with maintaining an EU database for the high-risk AI systems.

- A new test has been enshrined at the Parliament's request ('filter provision'), according to which AI systems will not be considered high-risk if they do not pose a significant risk of harm to the health, safety or fundamental rights of natural persons. However, an AI system will always be considered high-risk if the AI system performs profiling of natural persons.

- Providers of such high-risk AI systems will have to run a conformity assessment procedure before their products can be sold and used in the EU. They will need to comply with a range of requirements including for testing, data training and cybersecurity and, in some cases, will have to conduct a fundamental rights impact assessment to ensure their systems comply with EU law. The conformity assessment should be carried out either based on

internal control (self-assessment) or with the involvement of a notified body (e.g. biometrics). Compliance with European harmonised standards to be developed will grant high-risk AI systems providers a presumption of conformity. After such AI systems are placed in the market, providers must implement post-market monitoring and take corrective actions if necessary.

C. Transparency risks

Certain AI systems intended to interact with natural persons or to generate content may pose specific risks of impersonation or deception, irrespective of whether they qualify as high-risk AI systems or not. Such systems are subject to information and transparency requirements. Users must be made aware that they interact with chatbots.

Deployers of AI systems that generate or manipulate image, audio or video content (i.e. deep fakes), must disclose that the content has been artificially generated or manipulated except in very limited cases (e.g. when it is used to prevent criminal offences).

Providers of AI systems that generate large quantities of synthetic content must implement sufficiently reliable, interoperable, effective and robust techniques and methods (such as watermarks) to enable marking and detection that the output has been generated or manipulated by an AI system and not a human.

Employers who deploy AI systems in the workplace must inform the workers and their representatives.

D. Minimal risks

Systems presenting minimal risk for people (e.g. spam filters) will not be subject to further obligations beyond currently applicable legislation (e.g., GDPR).

E. GPAIs (general and high risks)

- GPAI system transparency requirements:

- All GPAI models will have to draw up and maintain up-to-date technical documentation and make information and documentation available to downstream providers of AI systems.

- All providers of GPAI models have to put a policy in place to respect Union copyright law, including through state-of-the-art technologies (e.g. watermarking), to carry out lawful text-and-data mining exceptions as envisaged under the Copyright Directive.

- Furthermore, GPAIs will have to draw up and make publicly available a sufficiently detailed summary of the content used in training the GPAI models according to a template provided by the AI Office.

- Finally, if located outside the EU, they will have to appoint a representative in the EU.

- Codes of practice and presumption of conformity:

- GPAI model providers will be able to rely on codes of practice to demonstrate compliance with the obligations set under the act.

- By means of implementing acts, the Commission may decide to approve a code of practice and give it a general validity within the EU, or alternatively, provide common rules for implementing the relevant obligations.

- Compliance with a European harmonised standard grants GPAI providers the presumption of conformity.

However, AI models made accessible under a free and open source will be exempt from some of the obligations (i.e. disclosure of technical documentation) given they have, in principle, positive effects on research, innovation and competition.

- Systemic-risks GPAIs (> 10^25 FLOPs) requirements:

- GPAI providers must notify the European Commission if their model is trained using a total computing power exceeding 10^25 FLOPs (i.e. floating-point operations per second).

- In addition to the requirements on transparency and copyright protection falling on all GPAI models, providers of systemic-risk GPAI models are required to constantly assess and mitigate the risks they pose and to ensure cybersecurity protection. That requires, inter alia, keeping track of, documenting and reporting serious incidents (e.g. violations of fundamental rights) and implementing corrective measures.

- Providers of GPAI models with systemic risks who do not adhere to an approved code of practice will be required to demonstrate adequate alternative means of compliance.

What is the scope of the EU AI Act?

The AI Act primarily applies to providers and users deploying AI systems and GPAI models in the EU market, as well as those located within the EU or third countries whose outputs are utilized in the EU.However, AI systems used for military, defense, or national security purposes are exempt from the current proposed regulation.

Additionally, AI systems developed solely for scientific research and development purposes are also not covered by the EU AI Act.

What are the "entry into force" timelines?

- Prohibited systems have to be phased out within six months after the act enters into force;

- The provisions concerning GPAI and penalties will apply 12 months after the act enters into force;

- Those concerning high-risk AI systems apply 24 months after entry into force (36 months after entry into force for AI systems covered by existing EU product legislation).

The codes of practice envisaged must be ready, at the latest, 9 months after the AI act enters into force.

In the coming months, the Commission is expected to issue various implementing, delegated and guidelines related to the act and to oversee the standardisation process required for implementing the obligations.

The full text can be found: here